How Push Came to Shove: the Little-Known Rise of Gruntruck

The act’s original manager (and storied Seattle record store owner) relates the enduring impact and legacy of “the most underrated band in Seattle music history.” This is part one of a two-part series Part two »

The initial seed of what created Gruntruck was planted in the summer of 1988 and early part of 1989 by friends Chris Cornell, Scott McCullum, and Eric Garcia. They were jamming at various spots in West Seattle with two bass rigs and two drum kits, rotating as they went… sometimes with two bass players and one drummer or two drummers and one bass, with vocal screams and grunts from Chris. They called it Bass Truck. It was all about making the most heavy, primal, pummeling, and tribal music they could.

Soundgarden had just been signed to A&M Records and after about a dozen sessions, Chris would find himself with some obligations to tend to… it was time to get Louder Than Love. Scott would get back to his band Skin Yard. In the spring of 1989, Skin Yard recorded the record Fist Sized Chunks. Scott asked his roommate/guitar slinger Tommy Niemeyer, from splatter punk kings The Accused, to guest on the track “Slow Runner.” Shortly after that, Ben McMillan, singer for Skin Yard, bumps into bass player Tim Paul at Lowell’s in the Pike Place Market. Tim was originally from Portland, had been in punk band Final Warning and had stints in famed punk legends Napalm Beach and Poison Idea. Ben asked Tim over to the artist collective known as SCUD (Subterranean Co-operative of Urban Dreams) and told him to bring his bass.

Ben was a fixture in the Pike Place Market. He was maybe more well-known as an artist and painter than he was the frontman of Skin Yard. He had a popular booth in the market where he sold his hand-painted shirts. These weren’t just typical shirts, they were very cool one-of-a-kind pieces. Ben was also one of the three founders of SCUD. He lived in the space too, in one of the studio units in the back. He was eligible for housing there because he was a working artist, not just because he was a founder.

SCUD, situated on the corner of Western Ave. and Wall St. a few blocks north of the market, was populated with writers, poets, clothing designers, graphic designers, mixed media artists, blacksmiths, actors, photographers, painters, and musicians. Those who didn’t live there worked in a studio there. It was basically an artists’ co-op. The SCUD folks governed themselves, with a French guy named Hugo Piottin—who also ran a very cool but short-lived all-ages venue (Metropolis) in Pioneer Square—at the helm. If you were a wannabe artist, the place was pretty intimidating. If you were a real artist, you were home.

The building housing SCUD was infamous for its Jell-O mold design, which along with the interior, was created by the artists themselves. There were hand-forged wrought iron structures surrounding the place. A café, originally called Free Mars and later the Cyclops Café, saw visitors like William Burroughs, Blixa, and Iggy Pop swing by when they were in town. Master illustrator and cartoonist R. Crumb said, “SCUD is a magical place, a treehouse of artists.”

With the café and open door, anyone was invited. There were a couple rehearsal studios down the hall. You would hear bands playing while having breakfast. It was a unique, raw, and instinctive environment. And for the Seattle art and music scene, it was ground zero.

Gruntruck was formed here. This was their headquarters.

With Tommy, you arguably had one of the great Seattle riff masters and with Ben, you had a genuine artist with great lyrics and a powerful voice. Tim gave it the balance, the rumble, and let it breathe. Scott, still reveling in his Bass Truck experience, made sure the sound was tribal and heavy. These would be well-crafted songs.

It was 1989.

The name of the band comes from Scott’s “Bass Truck,” with Ben, maybe thinking of the group’s guttural instincts, work ethic, and underdog mentality, swapping in “Grunt” for “Bass” and smashing the words together.

Click.

Gruntruck recorded Inside Yours at the legendary Reciprocal Recording studio. Jack Endino, guitar player for Skin Yard, produced. As Jack’s production career was in full bloom, it was clear that Skin Yard would be working around his schedule. He had already recorded iconic records for Sub Pop: Green River’s Dry as a Bone, Soundgarden’s Screaming Life, Mudhoney’s Superfuzz Bigmuff, Nirvana’s Bleach. He was on fire to say the least.

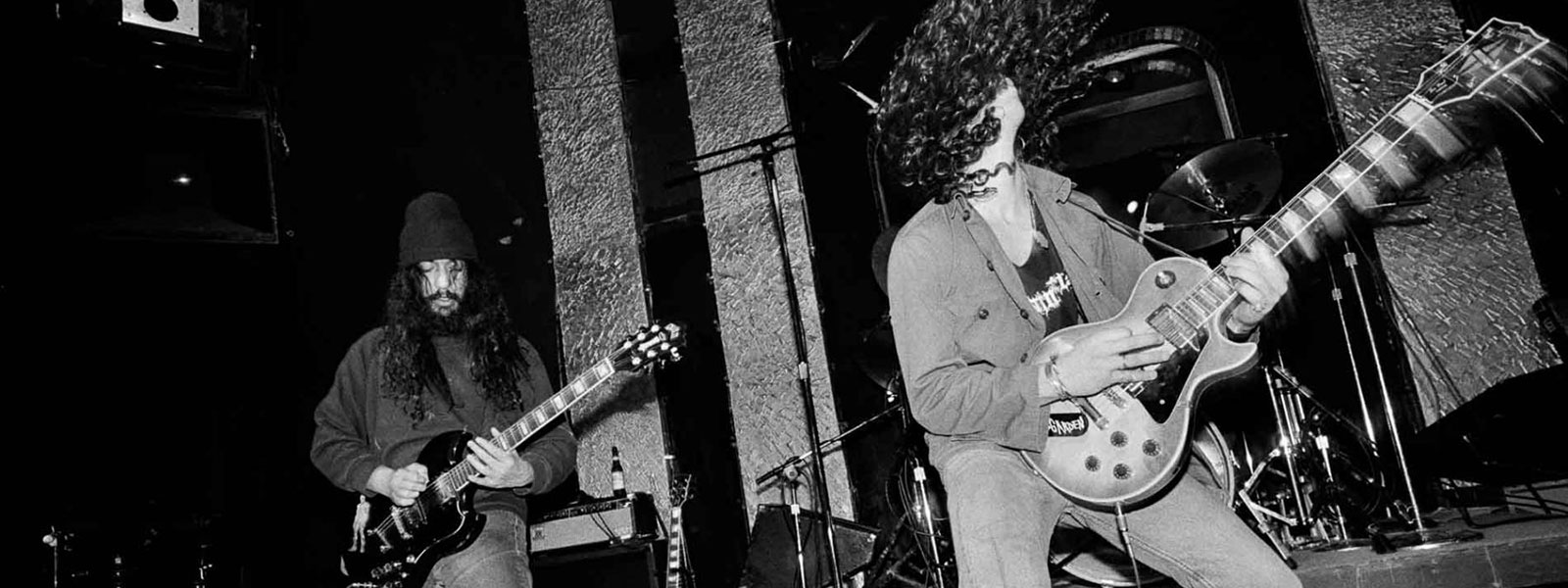

Gruntruck quickly became known for their energetic and powerful live performances. Photo credit: Alison Braun

At this stage, Ben and Scott were still committed to Skin Yard and Tommy was committed to The Accused. The band, considering Inside Yours a one-off that didn’t need to be shopped around, entrusted Blake Wright, owner of small local punk label eMpTy Records, with its release in 1990. (Yes, there were other labels in town besides Sub Pop.) Blake had by then released a successful Accused 7” as well as records by The Derelicts and The Fartz. (He would later go on to release records by The Gits, Supersuckers, and Murder City Devils.) The Accused was by then 10 years in, and Tommy, a founding member, had played countless shows with the band. They had paid their dues, were steeped in the skate-punk and hardcore scenes, and were friends and touring buddies with bands like GBH, DOA, and the Circle Jerks. They were local heroes—faster and more punk-rock than anyone else in town. But after a decade, it was unclear how much further Tommy could take them.

Given the positive response to Inside Yours and the encouragement from friends, Gruntruck decided to play a couple shows. I was helping the band with booking and anything else I could do in my spare time. At one point, I reached out to Sub Pop head Jonathan Poneman. A year before, Sub Pop had released the Skin Yard 7” “Start at the Top” for its Singles Club. The label was in the throes of its world domination, but even with such early success, they were struggling and it was unclear what direction Sub Pop might be headed. Even so, they were putting out great records and the staff and marketing angles were fantastic. I figured if Sub Pop was to show interest, Gruntruck would at least consider recording another record. Poneman passed. I don’t think he wanted to take a chance on what everyone assumed was just a side project.

When Roadrunner A&R exec Monte Conner asked Seattle man-about-town Jeff Gilbert (Pain in the Grass festival producer and contributing writer for The Rocket and Guitar World) what is the best Seattle band in town right now? Jeff said, “No fucking question: Gruntruck.” Monte flew from New York, met the band at The Offramp, and before the band even knew it, they were now a real band, they had been signed. I think I recall hearing that Monte offered them $8K cash and that was that. Gruntruck would be releasing another record.

Tommy was my first official employee at Easy Street Records who received a real paycheck. I let him work around his Accused schedule. Prior to Tommy, I would pay old high school buddies or neighbor friends to help out at the store, under the table. I could only hire guys because we didn’t have a bathroom. We would either run next door to West Seattle Speedway & Hobby and use theirs, or in an emergency, which happened a lot, we’d use empty bottles. Tommy lived in West Seattle a couple blocks down from the shop. We had a lot of fun in those early Easy Street days. He was my Sub Pop buyer and contributed a lot to the shop back then. Scott McCullum seemed to always be around and we all ran in the same circles.

I sat in on some of the recordings of Inside Yours and after they signed to Roadrunner, they asked me to manage them. I had just dropped out of Seattle University. I was very much stuck in slacker mode, a typical poster child for Gen X. I was looking to stake out my own claim, but there just didn’t seem to be a lot of opportunities. I was unsure what I was going to do. I was 22 years old and I’d already had the store for three years. Even though I was busy with Easy Street, I really didn’t see that I’d be doing it long term. I recall when my lease ran out, I didn’t ask to renew it.

You might ask, how did a 19-year-old have the gumption to start a business, with rent, buying inventory, etc? I had worked at record stores through my teenage years. One was owned by a stepdad on the Eastside, the other by a guy on the Westside. Both owners had to get out at the same time, for different reasons. I’ll leave it at that. I took the lease, fixtures, and inventory of the West Seattle store and the remaining inventory and name of the Eastside store. I had to keep the name of one of the stores otherwise I was going to have to file a business license and all that. There was no time for delay.

The Westside store I had worked at was called Penny Lane, a very unoriginal name for a record store. After a couple years, I moved it down the street (where it still stands today), created a logo, and hired a couple people. I guess I had a knack for running a record shop, knowing what records to buy, what labels to partner with, what bands to support. I assume that gave me some cred with some of the local bands and the overall scene, but what did I know about rock band management?

I actually knew quite a bit, it seemed. My boss in West Seattle had been the manager for Metal Church, a local band that went on to sign with Elektra and open for Metallica on the Ride The Lightning tour. (Killer metal band!) On the other hand, my mother Diana had been an independent radio promoter through the ’70s into the early ’80s, working with labels such as Island, Casablanca, Arista, Motown. In 1981, along with her husband Kim, she found local band Queensryche, got them signed to EMI, and managed their career throughout my middle school/high school years. I had an insider’s view into all this. In the case of Queensryche, I was often on the road with the band, pulled out of school to help out, do whatever needed to be done—photos, haul gear, be a young voice of reason.

Being brought up on Capitol Hill and later in West Seattle, I had a pretty keen view of that gritty Seattle scene of the ’80s and early ’90s. It was a beautiful collision of musical styles and ideas. Authentic, unpretentious, anti-establishment. Although we were adventurous and tenacious, we got labeled as “slackers.” I think we got dubbed this name simply because we had an aversion to authority. Anything that appeared fake, glamorous, or greedy, we wanted nothing to do with. The music reinforced those ideas and values.

As far as I’m concerned, Gruntruck’s follow-up Push best encapsulates that time, that spirit, and the reality that was.

Throughout 1991, Gruntruck played a lot of Northwest shows and was gaining quite a following regionally. Prior to recording Push, Henry Shepherd (brother of Ben Shepherd, from Soundgarden) would direct the video for “Not a Lot To Save.” It got some late-night views on local public access show Bombshelter Videos and even made it onto MTV once or twice. Roadrunner wanted to add two bonus tracks to the original eMpTy version and re-release Inside Yours internationally.

The band went into the studio with Endino in the summer of ’91 to lay down “Crucifunkin” and “Flesh Fever,” tracks they had originally intended for what would become Push. “Crucifunkin” would get some local airplay and would go on to become an encore staple. Roadrunner was thrilled, and Inside Yours had new life. (Both songs are included on the Record Store Day-issued expanded version of Push for a more complete look at the record and the period of time it represents.)

With rising airplay and a buzz about the band, I got a call from Pearl Jam manager Kelly Curtis. He asked me if Gruntruck was available to support Pearl Jam at the Moore Theater (January 17, 1992). This was essentially going to be Pearl Jam’s big coming-out party. They had toured small clubs under the name Mookie Blaylock and had supported Alice in Chains and Red Hot Chili Peppers, but hadn’t played a big show as a headliner.

We were all familiar with the guys in Pearl Jam and considered them all friends, but we didn’t know their singer, Eddie Vedder. Not a lot of people did, as he was still new to Seattle. We were all still sad over the loss of Mother Love Bone’s Andy Wood, and everyone knew that Stone Gossard and Jeff Ament had already accomplished a lot with Love Bone and Green River before that. Could they really do it again?

Jeff recently told me, “Not sure who suggested Gruntruck [for the Moore show], but it was likely me. Gruntruck was the first supergroup of our little scene. I used to see Ben in the Market every day on my lunch break, and Tommy was one of five people I knew when I moved to Seattle. I was so stoked when I heard they were playing together."

Prior to the show, Eddie tiptoes over to us in the opening act dressing room, introduces himself, brings us two cases of Rainier, bows a couple times, and mumbles something to the effect, “We should be opening for you, take anything you want from our dressing room, what’s ours is yours, thank you for helping us with this,” and he ran off. We all looked around thinking, This little guy is gonna get eaten alive.

Boy, were we wrong.

The Moore show was a magical night. Fortunately, Gruntruck held their own. They got a great reception and were immediately elevated onto new ground. As for Pearl Jam, this was the night they filmed the video for “Even Flow.” Nothing would ever be the same for them again.

A couple months later, Gruntruck returned to the studio with Jack Endino and master engineer Gary King co-producing. It was a perfect duo. We rented this movie studio, Red Farm Films, above the Pike Place Bicycle Shop—just down the alley from SCUD. Jack brought in a 24-track board. Gruntruck converted the space into their own private clubhouse. It was an ideal setting and the band would hang out there all day. Many of the songs were written there on the spot. For almost two months, this was their domain.

At the same time, I was converting an old boiler room in the basement of the Easy Street building into a full-size management office. I brought in good friend John McDonald to assist me. He had just gotten his accounting degree from Seattle U. We always had an intern or two helping out as well. I had speed bags, a basketball hoop, rehearsal space, refrigerator, and cold beer. Boiler Room Mgmt was born.

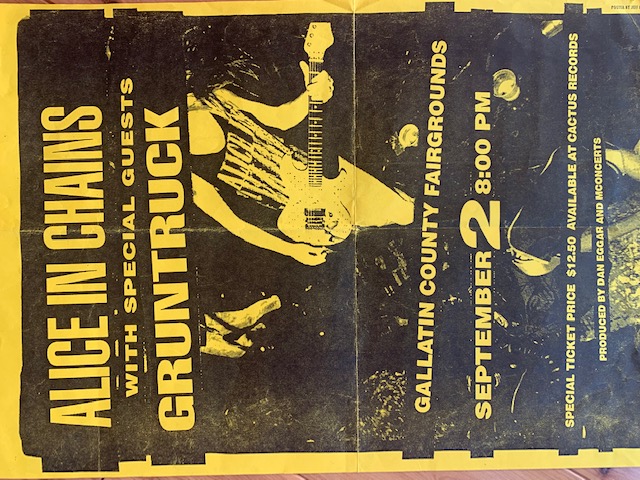

By then, Kelly felt that Gruntruck had made enough of a name for themselves to support the other band he managed (with Susan Silver, Soundgarden’s manager and Chris Cornell’s wife at the time), Alice in Chains. I have to think, too, that having Gruntruck opening would give Alice some additional street cred. Alice had initially been a little more glam, and with Dirt a couple months from being released on Columbia Records, they were very much part of the major label machinery. Their debut record Facelift had done better than expected, with opening tracks “We Die Young” and the iconic “Man in the Box.” Kelly asked if Gruntruck was available for what he was calling a “Shitty City Tour,” which would be two weeks barnstorming rural college towns across the northwest. We were in.

I recall Alice driving around listening to Push while Gruntruck trailed them listening to Dirt. Both records were set to come out in a couple months. This was going to be a great lil’ tour. Energy was high, the shows were club shows or in makeshift VFW halls, rec centers, and dilapidated airport hangars.

After the tour, the bands stayed good friends, going on camping trips and nights on the town. There was talk of bringing Gruntruck out on their Dirt tour, which was set to begin shortly after their record was released (September 29, 1992) and run through the rest of 1992. Push was to be released the following week on October 6. As excited as we all were to be touring together, this would be a costly venture for Gruntruck. Getting a tour bus, crew, and all the expenses that go with a full US tour… it was going to be a lot for us to handle. At one point, Kelly told me, “I don’t know what these bands have been up to, but Layne and Jerry are telling me that if Gruntruck isn’t on this tour, they aren’t going either.”

Roadrunner committed to supplying the tour support, but it was going to be bare bones. $10 per diems for each guy, fend for your own food, here’s your tour bus and some Motel 6 vouchers. Susan and Kelly were very kind and let us share their soundman and merch guy. They fronted us some $ along the way. Screaming Trees would be taking the middle slot.

The Singles movie and soundtrack were released in June of 1992. Alice had the lead track with “Would” and Screaming Trees followed it with “Nearly Lost You.” The soundtrack would go on to be one of the biggest-selling soundtracks of the decade. The Trees had also just released what would end up being their best-selling album Sweet Oblivion. Cameron Crowe’s cinematic love fest had an entire country enraptured by the Seattle lifestyle and the music that went with it. At the same time, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Nirvana were becoming the biggest bands in the world. Alice in Chains wasn’t too far behind. They would soon cement themselves in the pantheon of the great NW acts of the era. Dirt would be their masterpiece. It would eventually go on to sell 4 million copies.

Gruntruck was no stranger to opening up for the big boys, including Alice in Chains.

The Dirt tour started in Tampa Bay, Florida and scaled the entire country. Along the way, extra dates were being added and the venues were getting bigger. MTV followed the entire tour, trailing us in their own tour bus. Gruntruck was on the most hyped tour in the country. With Gruntruck being the most accessible of all the bands, they got a tremendous amount of press. They were also going over very well with the Alice in Chains audience and Alice were their biggest supporters. There wasn’t a night where one of the guys from Alice wouldn’t be wearing a Gruntruck shirt on stage.

Screaming Trees were having some internal issues. At one point Mark Lanegan left and Screaming Trees took a week or two off—and Gruntruck was the sole opener again. Eventually, the Trees would regroup and finish the tour, but there was obviously some unrest within that camp. The tour ended days before Christmas, with two sold-out nights at the Seattle Center Arena (December 19 and 20).

This tour was a little bit of a double-edged sword, though. Gruntruck had gotten a taste. The band was on a high after being on such a great tour—beyond sold-out every night, great reception, new fans. They got an endorsement from Gibson Guitars, did photo shoots, appeared in magazines, and signed with booking agent ICM.

We’re on our way now. It’s only going to get better, right?

Gruntruck’s Push is finally being issued on vinyl for the first time domestically on Record Store Day (June 12, 2021). It’s a two-LP set with enhanced packaging. Two bonus tracks. Remastered by Jack Endino. Courtesy of Real Gone Records, in association with Rhino Records and Universal Music.

Matt Vaughan is the former manager for Gruntruck and the owner of Seattle's Easy Street Records. He lives in Seattle.