How Push Came to Shove: the Little-Known Rise of Gruntruck

The act’s original manager (and storied Seattle record store owner) relates the enduring impact and legacy of “the most underrated band in Seattle music history.” This is part two of a two-part series. Read part one here

Roadrunner was known as a metal label. Known for acts such as Mercyful Fate, Obituary, Sepultura, Type O Negative. They were trying to diversify and Gruntruck was the ticket that could get them into the mainstream. Unfortunately, the label didn’t have the radio promo punch yet and their distribution and promotion network lacked the reach. Moreover, here was a metal label from New York City trying to work a rock band from Seattle.

There was a great staff of hard-working folks there: Monte Conner, Kathie Merritt, Scott Givens, and Susan Marcus, but they were challenged and we could see that there was a struggle getting airplay and records in the shops. The traditional metal promo machine didn’t necessarily work for Gruntruck, albeit Gruntruck did have more of a metal edge than any of the other Seattle bands.

We could see bills mounting and there weren’t any royalty payments and it didn’t appear we would ever get any. I started diving into the contract. I sought help from Susan Silver and entertainment attorneys. I read every music business book I could. This was a bad deal. I talked with other Roadrunner acts and found that apparently this was just the way it was. Really? Oh, no. This was one of those 360 deals you’d hear about. It was clear this deal needed to be worked out or the band needed to leave the label.

Other record labels were letting me know their interest in Gruntruck, so I started taking meetings. Discreet meetings. It was a conflict of interest for another label to engage with a band that was already signed. The original frontrunners were Geffen, Polygram, and EMI. Inevitably, these A&R guys would get cease-and-desist letters from Roadrunner. We tried to broker a deal where Roadrunner could act as a subsidiary to one of the majors, like Sub Pop did with Geffen and Nirvana. Whatever we tried, Roadrunner was reluctant to let Gruntruck go. They had a plan for the label and Gruntruck was an important piece of that plan.

Even with this contract business to deal with, it was obvious that Gruntruck had arrived and the band felt confident that they belonged. There were a lot of great things at hand and 1993 was shaping up to be a great year.

We had hoped to join forces with Alice and Screaming Trees on the European tour, but it was proving too costly for us. Also, I think that Susan Silver knew that by having Gruntruck on tour, it wasn’t going to quell any of the shenanigans that were going on. Not that Gruntruck were into super-hard drugs or filming sex acts in raunchy motel rooms, but let’s just say it was a little risky. They were too good of friends and there was a lot at stake. Furthermore, they didn’t want to be liable for a band that might have to borrow money along the way. Alice and the Trees would head out to Europe and Alice would embark on a relentless pace throughout the rest of the year, eventually headlining the Lollapalooza tour.

No biggie. Once home, we soon got word that we were going to Europe, too. We were invited to be the sole opener for Pantera. They had released Vulgar Display of Power on Atlantic Records. Vulgar was (and still is) one of the greatest metal records of all-time, and was produced by Seattle’s Terry Date. He’d also produced Metal Church, Mother Love Bone’s Apple and Soundgarden’s Louder Than Love and Badmotorfinger.

We only had a month before the tour started, and given the short time to prepare and the foreign setting, I didn’t feel comfortable tour-managing. On the Alice tour, I knew everyone, knew the language, the currency, the American way. On this one, the tour manager was also going to be the driver. It’s tough enough to manage a tour, but I wasn’t ready for all that. (I also still had my record shop to run and quite honestly, being on tour was unsettling for me. I was a homebody.) We needed someone with experience in Europe.

ICM recommended a tour manager who had worked with Ministry and Skinny Puppy and had been all over the world. Dan, the tour manager, lived in Vancouver, BC. He drove down I-5, stayed with me for a couple days, and we prepared for the tour. He was going through a breakup with Sarah McLachlan. I recall he was obsessing over his breakup more than the tour at hand. He was a softy, and here he was about ready to go out with Gruntruck and Pantera!

The tour ended up being a major success. Gruntruck rose to the occasion, Pantera loved them, and they were growing their fanbase. As for that tour manager? When I picked him up at Sea-Tac Airport, he looked like he’d been run over by an 18-wheeler. We never heard from him again.

Soon after the European shows, I got a call from a Coca-Cola exec asking us if Tommy could be used in a commercial for their soft drink Mello-Yello. It was Coke’s version of Mountain Dew and was popular throughout the Midwest and the South. Tommy would get a good amount of $ for it and the band would get a little bit, too. We accepted. With Tommy’s punk-rock dreads and legit rock-star looks, he was featured prominently. The spot was directed by Barry Sonnenfeld, who had just finished the film adaptation of The Addams Family and would later do Men in Black.

The band was planning on working with The Jim Rose Sideshow on a video for “Crazy Love,” but Roadrunner had other ideas. They were flown down to LA for a video directed by Darren Lavett, who had just done the Beastie Boys’ “So What’cha Want.” It was a bit of a blur and a hassle, not the less-expensive, local approach we’d wanted to take; another costly sinkhole staring at the band. But we already owed so much money, we just went ahead with it.

One big problem: Tim Paul was just kicked out of the band.

The reasoning didn’t make a lot of sense to me. It went from something as minor and ridiculous as “he smokes too much” to “he isn’t part of our drug culture.” In other words, he doesn’t do cocaine. As I saw it, Tim was just more mature. He was a bit of a loner, but he very much loved Gruntruck and repped it every day. Great bass player, too. The sludgy rumble that Tim brought to the band would soon be gone. Not only in his bass playing, but also his presence. He balanced the band like only great bass players know how to. He opened it up, had a cool groovy style, and he complimented the other players.

I still feel terrible about that. As a fan of so many bands, it has always rubbed me the wrong way when a band fires a founding member. The cracks in the Gruntruck armor had started to show.

Alex “Maggotbrain” Sibbald was brought in. Alex had been in The Accused with Tommy, was a master musician, a gearhead, lived in West Seattle, and owned the popular rehearsal compound Crown Studios. We all liked Alex and knew him well. It wasn’t like he was pining for the slot, he was asked to join the band.

Off to Hollywood for a video shoot.

ICM booked us a spring tour. We’d be opening for Columbia Records act Circus of Power, a hard rock/biker band out of NYC. They had success with their two previous records, but bands like theirs were becoming casualties to the huge Seattle scene and here they were, on tour with one of the best. Plus, with this tour there was no hype, there was no excitement. We witnessed the slow demise of Circus of Power while on tour. In some markets, the shows were changed to co-headline gigs.

One night, our landlines started blowing up. MTV’s Beavis and Butt-Head was showcasing Gruntruck’s “Crazy Love” video! Mike Judge’s animated Gen X sensation centered on two hesher kids from Texas ridiculing, sneering, and making fun of music videos. But when they watched the Gruntruck video? It was “These guys rock,” “This kicks butt,” “I can’t believe they are playing something cool,” and “it doesn’t even suck.” Thanks in large part to those characters’ reaction to the video, it would get onto MTV rotation and be re-run on the show the rest of the year.

We were back home for a while and the band was able to bask in their local stardom. Even though they owed all these recoupable costs back to the label, it was a long-term contract and they weren’t owed back anytime soon. The guys could make money in the meantime, quit whatever jobs they had, and settle up any personal business. They could at least afford the basic means of survival.

I was booking local shows and small NW regional tours and we were side-hustling merch. We were able to command 100% of the door, with no splits back to the clubs. I even found myself successfully negotiating for a percentage of bar sales. Gruntruck brought drinkers to the club! A sold-out RKCNDY show could generate the band $12K. Their merch could bring another $3K. Local and regional radio were playing “Crazy Love,” “Tribe,” and “Above Me.” Jocks Scott Vanderpool, Cathy Faulkner, Rockfish, Marco Collins, and Damon Stewart were all massive supporters. “Crazy Love” would go on to be the #1 most-requested song on Seattle’s KISW in 1993.

I was talking with ICM and Roadrunner about possible summer tours. Kyuss and Danzig were being discussed. But ultimately we decided to stay home, to make money rather than lose it. It also gave us a chance to do some housekeeping in the comfort of the NW, which had completely wrapped its arms around Gruntruck. We needed to figure out what was happening with our relationship with Roadrunner.

The label was struggling to get the band airplay and record sales—yet was demanding a new record. On top of that, the list of interested labels was growing and these labels were more in line with a band like Gruntruck. Local law firm Bogle & Gates took us on pro-bono in an attempt to work something out with Roadrunner. There were a couple fan-boy attorneys at the firm who negotiated to get a salary for each band member and get rehearsal expenses covered. So for the next 6 months and into early 1994, each guy would do alright financially... but again, these were recoupable costs that were owed back to the label. At some point, we see that Roadrunner has us owing them $250K.

Roadrunner did finally agree to try a subsidiary deal, but only if it was with Epic. I flew out to NYC and met with their A&R hotshot Michael “Goldie” Goldstone. He had signed Mother Love Bone while at Polygram and then signed Pearl Jam and Rage Against The Machine at Epic. After I waited in the lobby for an hour, he arrived and said, “Why am I meeting with you?” Then it was, “I already have Pearl Jam and Rage Against The Machine. Why do I need your band?” I tried to convince him otherwise, and little did I know that PJ’s Mike McCready had called Goldstone himself and pleaded that he sign us. Still, there would be no place for Gruntruck at Epic, they were stacked. They didn’t need us.

Other things worked out better. MCA Concerts called and asked if Gruntruck would headline The Moore Theater on June 26, 1993. Of course! It was a sold-out show and we had friends Lazy Susan and Truly open up. Truly was Hiro Yamamato from Soundgarden, Mark Pickerel from Screaming Trees, and local songwriter Robert Roth. They had just been signed to Capitol. Lazy Susan were a phenomenal band and featured great local singer Kim Virant. After Gruntruck’s third encore, my MCA rep came up to me. “I might have something bigger for you next time,” he said. They would indeed.

Between shows and Push continuing to sell throughout Seattle and the NW, we were grabbing new fans while retaining the old ones. The original fan base consisted of artists and musicians, hippy chicks, and street-tested urbanites. Many of the early shows were promoted as “Gruntruck: A Psychedelic Skull Crunching Amphetamine Love Bash.” Our friends at SCUD created these psychedelic, liquid-light shows projected on a screen behind the stage. It was something out of the Fillmore and Haight-Ashbury scene. It was a trip-heavy experience. There was this love-child imagery of peace, progress, and unity… but the music was still bone- crushing.

Gruntruck's Push. The band's final full-length album.

Gruntruck and Push had touched on something. Ben’s groovy, catchy, psychedelic lyrics and twisting staccato guitar style... the rumbling, knee-breaking rhythm section... Tommy’s chunky, jigga jigga street-punk riffs... it was all cemented in gritty old Seattle amid the original hippies, Pike Place merchants, rain, big jet airliners, big trees, big mountains, peep shows, Bukowski-soaked poetry, junkies, skate rats, and smelly fish mongers. It made for one of the most convincing and purest examples of the “Seattle Sound.” The fact that these guys were seminal figures rooted at SCUD, part of the early club scene, and that Jack Endino was their best friend… it was about as legit as it could ever be. They played faster and heavier than most, the song craft was mature, and they were proud of their Seattle heritage.

From the chorus of Push’s opening track “Tribe,” it was clear they were there for the counterculture outcasts, the grunts, and all the freaks: “I just want to fly my freak flag, c’mon join our tribe.” They were also harkening back to the spirit of hometown hero Jimi Hendrix and his similar sentiment in “If 6 Was 9”: “They’re hoping soon my kind will drop and die, but I’m gonna wave my freak flag high.” Like those who had come before them in Seattle, Gruntruck was about pushing through, about doing it together. Being who you wanted to be. Ambition, art, music.

This was reflected in the iconic record cover. Ben body-painted his girlfriend Lori Smith in psychedelic designs, including a backwards American flag on her face. SCUD photographer Cam Garrett captured the shot, in which Lori wears a studded belt and grips a colorful toy truck. Though it was a slippery slope to put a half-naked woman on an album cover, there was no question this artistic statement was pro-woman. It was also a far cry from records made by other Seattle acts then that featured black and white or fuzzed-out imagery. Push’s cover was vivid, inviting, and inclusive. There was a message there: it was time for Seattle to open up.

Fittingly, a lot of Gruntruck’s new fans were from a different crowd. The band was resonating with blue-collar folks. To me and the rest of the band, these were just regular guys: dock workers, machinists, mechanics, carpenters… but Ben was unhappy with how aggressive some of the attendees were getting and wondered where all the “knuckleheads” were coming from. I would say, “Ben, listen to your lyrics.”

Yeah we’re poor and living hard, while the others are living large

Punchin’ the clock until my knuckles bleed, punch, punchin'

Too many jobs and a demon boss, I gotta get away

“These guys just had a long day at work and now they’re here,” I told him. “These are your people, this is your tribe.” The band was becoming the voice for every laborer and anyone with a tool bag. At the same time, while some of the other Seattle bands were slowing it down, Gruntruck was speeding things up—machine-gun power chords, cymbal crashes, a heavy dose of full-steam liberation.

Gruntruck were great players and put on great shows. A lot of up-and-coming young musicians were inspired by them. While the local big bands were out on world tours, Gruntruck was in town, walking the streets, playing clubs. One example: a “Bored as Hell” Seattle tour where they played the Offramp, RKCNDY, and King Cat Theater all in one day. Each show sold out.

The band was accessible and engaging, appealing, honest, and could relate to the fans. They weren’t moping or brooding, they weren’t depressed, nobody was using heroin. While the Big 4 (Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Nirvana) were winning Grammys, going on SNL, getting MTV Unplugged sets, and buying big-ticket toys, Gruntruck was becoming the people’s champ. The underdog.

But Ben didn’t want to be the underdog anymore. He felt that he had paid his dues. His band Skin Yard was on the legendary Deep Six compilation (1986) with the Melvins, U-Men, Malfunkshun, Green River, and Soundgarden. He was OG, approaching his mid-thirties, and didn’t feel that he could keep waiting. In a way, Tommy felt the same way. Both guys had put in the time and effort and that’s exactly what Seattle loved about them. It was their cross to bear. Seattle was keeping this one to itself.

The band was writing new songs and we were accepting good-paying one-off regional gigs. These always went well and would give the band an adrenaline rush. We were very much flying as a DIY act now, setting these gigs up on our own, without our agent. We were getting our own press, radio play, records in the shops, handling our own merch, starting a fan club. I was feeling good about where we were at, but there was some risk that came with it.

I accepted a proposal from a young promoter in Spokane. He was trying to do an outdoor festival in October of 1993, with Gruntruck as the headliner. I hadn’t heard of any of the other bands he had on the bill. He assured me they were well-known Spokane bands. We asked if our friends Coffin Break could at least be added to the bill. OK, at least there’s someone there we’ll know. The promoter offered our band $5K for the gig.

The morning that we started the 600-mile road trip for the festival, I still hadn’t seen the advance money come through. Then we get there for soundcheck and there’s about 50 people scattered across this massive lawn. We were expecting 2-3,000 people. I was getting nervous. The promoter, dressed in a robe, told me not to worry. “Spokane people show up late,” he said. “We’ve played Spokane. They don’t show up late for Gruntruck,” I shot back. My partner John and I started to prepare for an Irish-mob takedown on the guy. After a handful of terrible acts, one of them a cover band, Coffin Break played—and there was still nobody here. We delayed our set time, thinking more people might show. In the end, there were about 100 people on the lawn. The weather was bad, the show was bad, it was just all bad. John and I cornered the promoter and grabbed the cash he had, which was all of $500. I gave Coffin Break $200 and because we couldn’t afford to stay the night in Spokane, we headed home.

On Snoqualmie Pass, John and I came upon our van and trailer broken down on the shoulder. A couple of the guys had already hitched it for Seattle. I sat on the side of the road with the others, reflecting on my worst day as a band manager. I took a couple hits of Alex’s chronic and by the time AAA showed up, it’s pouring rain, it’s dark, it’s late, and I’m stoned.

As I drove west on I-90, a deer hopped out, I hit the brakes, and my Honda CRX does a full 720 at 90 mph. John drove us the rest of the way home. I looked out at the darkness as the miles shortened ahead of us and wondered if this was the beginning of the end.

Thankfully, not a lot of folks heard about that outing. It was as if it didn’t happen. A week or so later, I got a call from MCA Concerts: “Are you guys ready for The Paramount, New Year’s Eve?” It’s one thing to headline the Moore, but the Paramount? For hometown kids, that was the mother church. And I was thrilled that Gruntruck was still relevant, that our dud in Spokane hadn’t turned everyone off. I ironed out some details and called the guys to share the good news. They could certainly use some.

Instead, Tommy gave me bad news. They’d just kicked Scott McCullum out of the band.

I wasn’t totally surprised. I’d been aware of Scott’s frustration with Ben and Tom, the two faces of the band. Scott didn’t feel that they were speaking for the band as a whole, especially when it came to press and interviews. A great conductor and writing partner, he had also been questioning the direction the band might be headed. Knowing he was essentially the founder of Gruntruck, he wasn’t quiet in trying to keep things in line. It frustrated him, too, that Ben and Tom were in a bit of a power struggle with each other, making it twice as hard for anyone else in the band. Tommy put Scott out of his misery.

Alex and I tried to get Scott back, but the damage had been done. Now what? We put a quick “Shitty City” tour of our own together, with it ending in Seattle on New Year’s Eve. This gave Gruntruck time to play with new drummer Ollie Klomp, a master percussionist and part of the Critters Buggin scene.

Ben and Tom were calling the shots now, and were maybe even more committed than ever before. In a way, it was easier dealing with just the two of them than it was four. Everything we planned for the Paramount show on New Year’s Eve went off like a dream.

We had Green Apple Quickstep open. They were signed to Reprise, their upcoming record was being produced by Pearl Jam’s Stone Gossard, and they had a song on The Basketball Diaries soundtrack. Legendary illustrator and graphic artist Frank Kozik did the show poster. KISW sponsored. We were able to rehearse a proper light show and have the crew we always wanted, even if for just one night. All our friends, family, local bands, and everyone that had been part of the Gruntruck journey were there. Sold out! It capped off what had been a crazy two years.

The next two years, 1994 and 1995, would be exercises in patience and will power, determination and resilience. To make it through, the band would have to push harder than ever before.

It was clear there was no way the band was going to ever make a living while being obligated to the Roadrunner contract. Bogle & Gates said that Gruntruck’s future albums would have to go platinum to allow the band members to make a modest living. So it seemed the only course of action was to have Ben and Tom file suit against the label.

My talks with other labels continued. There was Geffen’s Mio Vukovic, who had signed Urge Overkill. In the case of EMI, it was the VP himself Daniel Glass that wanted the band. He jotted down the basics of the deal and said, “This is the same deal we gave the Red Hot Chili Peppers.” We’d soon have Seymour Stein from legendary Sire Records interested as well. He had signed The Ramones, Talking Heads, and The Replacements, to name a few.

On April 5, 1994, Kurt Cobain died. We were set to perform in Wenatchee and were all watching a Sonics game on TV in a motel room when the news broke. It was a shock and bummed us all out. Ben had been friends with Kurt and he struggled with the loss.

Kurt’s suicide was only the most recent in a string of unsettling tragedies and developments. Riot grrrl Mia Zapata from The Gits had been raped and murdered on July 7, 1993 a few blocks away from the Comet Tavern. Layne Staley was in and out of rehab, which put Alice in Chains on hiatus. Bands were getting dropped, breaking up, or floundering, but somehow, Gruntruck kept pushing.

Ollie was let go of the band and Steve “Slayer Hippy” Hanford was brought in. Steve was arguably one of the best drummers in the NW. He had not only been the drummer for Poison Idea, but also their producer. Their 1990 record Feel The Darkness was a hardcore punk masterpiece. Steve produced a lot of Portland acts, including Elliott Smith’s Heatmiser. I gave him keys to the Boiler Room behind Easy Street and he brought his drum kit in and practiced there.

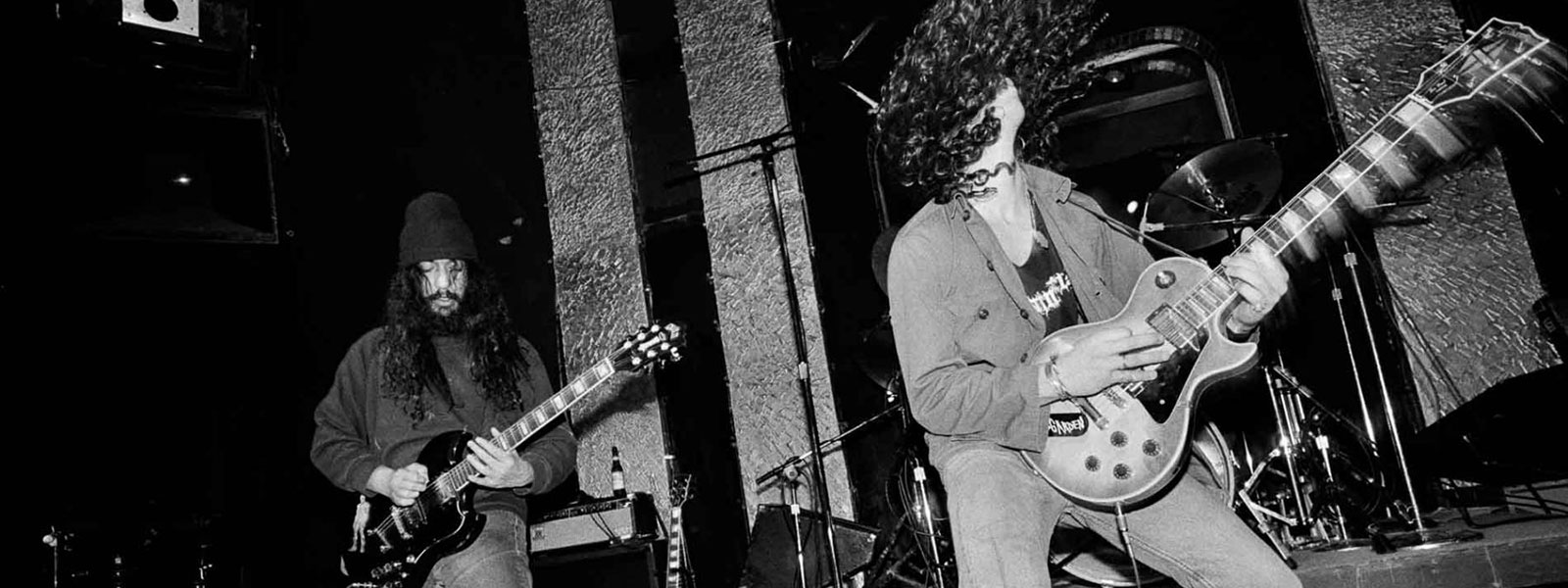

Gruntruck. Photo credit: Alison Braun

At first, it seemed there was no stopping this new Gruntruck. It was a little more snappy, with rapid-fire double kicks and everflowing fills. We were all on board. If we thought the shows were frenetic before, these were all-out assaults. The band was pushed to the limit and they liked it. But one afternoon I walked into the Boiler Room and Steve was slumped over his kit, talking in a baby voice with his eyes in the back of his head. He was a big guy and I’m trying to get him on his feet. He was nodding off. He eventually comes to, acting as if it was just a normal day. Unfortunately, for him it was. He was a serious heroin addict.

Steve was replaced by Josh Sinder. Josh, like Steve, played as if he was on the drag strip. Joining Gruntruck in the midst of a label conflict was nothing new to Josh, as his band TAD had had its share of label problems and public lawsuits. (Polaroid-photo lawsuit, Jack Pepsi lawsuit, Bill Clinton smoking a joint… they couldn’t catch a break.) He made it seem normal and helped downplay our own issues. Josh was a great friend of the band and he had been in The Accused with Tommy and Alex before joining TAD. So Gruntruck now consisted of three ex-Accused members and Ben.

Somehow, Ben was able to work with this new rhythm section while also placating Tommy. He was able to find hooks and choruses in the new material they were writing. It was faster, with razor-tight precision, but surprisingly, it was working. Ben himself was in great spirits and maybe at his creative peak. Around that time he developed a renewed sense of ambition, mortality, and determination. He went to the gym, read Nietzsche every day, ate well, tempered his drinking and drug use. His sister had died at a young age and much of his family had serious health issues, and I think that weighed on him.

Roadrunner would cave in a little bit. The label agreed to rework the publishing deal, but it just wasn’t enough. Once the lawyers started going back and forth, it got messy. The label held its ground, trying to prove that no other band could ever think of doing such a thing.

But after a grueling year, Gruntruck won the case. It was determined in summary judgement:

Gruntruck was an honest debtor and must be relieved from the weight of oppressive indebtedness and be permitted to start afresh free from obligations. Involuntary servitude violates the spirit of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Whoa! Of all the things that Gruntruck accomplished, this might be their greatest achievement. The legal case would affect the way such contracts were written from then on, and is still well- known in music business law and is referenced to this day. Their long grind ultimately was a win for all musicians and bands.

The toll this took on the band was hefty, though. They had been deep in the belly of the ugly music business. They came out alive and free, but now what? It was time to release some of new music.

Back in the studio with Jack and Gary. The songs were crisp. Still great hooks. It wasn’t as rumbling and tribal as before, but it was clear that they weren’t settling or slowing down. Local radio jumped on them all over again. We put out a 3-song CD titled Shot on our own. The same labels were still interested and we could now talk freely with them. Gruntruck was back—and in control. The summer of 1996 was looking good and they had many opportunities in front of them.

We had been asked to open for Alice Cooper at the Gorge, arguably one of the greatest venues in the entire world, on July 4. Not only was the band beyond honored to perform in this awesome canyonland setting, but in support of one of the greatest rock legends of all time, and to all members in the band, a true musical hero. Tommy, for one, brought all his old 8-tracks to get signed. We weren’t the only ones that showed up early, though. We see this guy hitting golf balls off the Gorge into the canyon. (We later heard that they were biodegradable.) This guy was good, majestic. After about an hour, the guy comes walking up to us. We’re all playing basketball in the parking lot. It’s Alice fucking Cooper. “Hi boys, throw me the rock.” He drops his golf bag. “I’m from Detroit, you can’t stop me.” Swish! I grab the ball. “Hey Al, make it take it.” Before he can hit his next jumper, we see this attractive older woman on the hill on the porch of the guest house. She has a couple kids next to her. She yells, “Al, The Simpsons are on.” “Boys, I gotta go, thanks for being here, see you on stage.” Al walks away and up the hill. We were speechless.

The following day, Gruntruck headlined one of the summer’s Pain in The Grass festivals at the Mural Amphitheater in the Seattle Center. It was a fitting setting, under the shadow of the Space Needle. With a couple thousand people in attendance, it was a warm and resounding sendoff, as we set to embark on a West Coast tour.

We had booked our own tour. It would end at the legendary Troubadour in LA. We’d meet all the labels there, we’d pick the one we wanted, hang out in Hollyshmooze, get our attorney to look over the contract, then finish the record and be on the next Lollapalooza. Good plan, right?

The tour went well. We did it DIY-style, had a solid crew, sold a lot of merch—including the Shot CD, which finally gave fans new music. We brought along our friends The Lemons to open the shows. They were on Mercury Records, their record had been produced by Bill Stevenson (from Descendents fame). I’m sure we relished the idea of having a major-label band opening for us.

When Gruntruck wasn’t playing, they were meeting with radio, press, retail. At some point, I heard that Mio Vukovic was no longer at Geffen (guess that Urge Overkill signing didn’t go as well as they’d hoped). Daniel Glass had been fired and the EMI label was in limbo. But there was still Seymour Stein at Sire and all the other A&R scouts would be at the Troubadour.

Once we got to LA, though, something didn’t feel right. The band didn’t seem excited. I tried to do my best Vince Lombardi on em, but they weren’t having it. I’m going on about the journey and that we’re finally here. We were sitting in this legendary dressing room at one of the most storied venues in the world, I was going on about the roads we’ve travelled, the struggle they endured, the grit they showed, and now here we are… and I was thinking I shouldn’t have to work this hard.

Knowing what the labels wanted to hear, I drew up the setlist. It got off to a slow start. Josh was off, dropped his sticks, then had to re-tune his kit. Alex had his back to the crowd, then Tommy did, and Ben was writhing and rolling on the stage in some bad Jim Morrison routine. Wha? They weren’t going off the setlist, talking amongst themselves between songs. It was the worst show they’d ever had, maybe even worse than Spokane. It was a nightmare. They were sabotaging their career. I was stunned, perplexed.

My little sister Aimie and all her friends were there doing their best to act as if this was the greatest band they’d ever seen. They were the only ones acting that way, and it wasn’t flying. Seymour Stein got my attention from across the room. He shook his head, gave me a death-knell stare, and walked out. It was over.

The band drove back to Seattle. I had already planned on staying in LA for a few days anyways, thinking I’d be negotiating a record deal. Instead, the next day I went for a long bike ride from my sister’s place in Long Beach down the 101 to Zuma Beach and back. Along the way, I reflected on these last 5 years with Gruntruck. All the shows, the nights in the studio, the miles on tour, the practical jokes, the adrenaline rushes, the adoring fans. By the time I got back to my sister’s place, though, I knew I had come to the end of my journey with Gruntruck. It was time for me to recalibrate, handle my own life, and put my energies back into Easy Street. I still had unfinished business there.

There would still be one last show on the itinerary, however. Back home, in Seattle. Gruntruck played Moe’s on July 26, 1996, to a packed house and a mass of people on 9th and Pike trying to get in. Tommy and I had put a lil’ pre-show playlist together and delayed the start time a little bit, which only put the fans into more of a frenzy… Isaac Hayes’ “Shaft,” “Black Sabbath’s “Supernaut,” Devo’s “Mongoloid,” Vandals’ “Urban Struggle,” Ennio Morricone’s “Ecstasy of Gold.” By the time Gruntruck entered the stage to “Going the Distance” from Rocky, the crowd was in full exaltation. This would be one of their finest shows. It was Gruntruck in all their glory.

In the end, the band and city were too tight to be separated. It very well may be that Gruntruck wanted it to be that way, too. They didn’t really want the big record deal after all, the big-ass tour bus, opulent hotel rooms, fancy clothes. They were at their best when they were struggling, when they were pushing. They stayed true to their roots. That authentic, anti-establishment, raw honesty… it was still all there and it reared its head that fateful night in Hollywood. They couldn’t shake it, they couldn’t fake it. They were still street kids at heart and didn’t want to get on board, after all. They really were doing it for the music. They were a true-blue Seattle group, and in my mind, remain the most underrated band in Seattle music history.

Deep down, Gruntruck knew (as I did) that the Troubadour basically spelled the end—and in many ways, symbolized the massive shift in the Seattle rock scene of the previous decade or so. Alice in Chains was a question mark. Soundgarden was not far from breaking up. Mudhoney was soon to return from its major-label experience to a revamped Sub Pop. Screaming Trees would split up and Mark Lanegan would go solo. Dave Grohl would emerge from Nirvana’s demise with the self-made band Foo Fighters.

There were a handful of Seattle hopefuls: Sweetwater, Green Apple Quickstep, Truly, Goodness, 7 Year Bitch, Seaweed, Love Battery, and so many others... they’d all get dropped or break up. The Presidents of the USA would thankfully bring some levity with smash hits like “Lump,” “Peaches,” and “Dune Buggy.” Stone Gossard from Pearl Jam would sign desert rockers Queens of the Stone Age to his Loosegroove Records. Queens would become one of the great rock bands to come out of the late ’90s. The whole aesthetic was shifting. Roadrunner would go on to to sign Nickelback and get the mainstream success they had been searching for. Madonna’s label Maverick Records would sign Candlebox. A bubble-gum flavor of Seattle would sell through the last part of the ’90s and into the new millenium with bands like Fuel, Bush, Staind, and Puddle of Mudd.

After Soundgarden’s breakup, drummer Matt Cameron would join Pearl Jam, arguably the greatest rock band of the generation. They have the rare distinction of being inducted into the Rock n Roll Hall of Fame on the first ballot. It’s an honor they deserve for the great music they continue to make and their ongoing engagement with social and political causes. Pearl Jam’s fanbase is unlike any other, and the band itself is a lasting reflection of Seattle and what it stands for.

It could be said that without Chris Cornell, there never would’ve been a Gruntruck. He helped light the fuse and was part of its inception. We all miss you, Chris.

The original Gruntruck lineup of Ben, Tom, Scott, and Tim would eventually reunite. They played a handful of well-received shows and spent some time in the studio, but Ben was starting to have serious health issues. His condition deteriorated even as he wrote songs and painted. Ever the artist, Ben McMillan died in 2008 due to complications caused by diabetes.

Whenever I walk through Pike Place Market or Belltown, I can still feel Ben’s energy and the untamed excitement of yesteryear. He was what it meant to be an artist in Seattle. Miss you, Ben.

Cyclops Cafe, Seattle

The SCUD building was demolished in 1997, but its spirit lives on with a standalone Cyclops Café that opened in 1999 by original SCUD artists John Hawkley and Gina Kaukola. It’s just down the street from the original SCUD location. Go see em at 2421 1st Ave.

There never would be a proper follow-up to Push. And that’s how it was meant to be.

The acclaimed author Charles Cross recently said, “Gruntruck were always one of my favorites, they were unaffected, they weren’t as self-aware. Their sound mixed metal, hardcore, and garage stylings… it was pure Seattle. The unassuming nature of the band and their exciting live shows helped win them a massive Northwest fan base. Even if Push didn’t sell millions, in the end maybe that’s for the better: the kind of classic record that can be discovered years later. Push instantly brings back the power and the fury of the Northwest in the nineties.”

Thankfully, Seattle has remained an artistic community and while other music scenes have come and gone, this city has continued to create great music and internationally renowned acts. As far as the music revolution and cultural impact of what bands like Gruntruck helped create in those late ’80s and through the ’90s? That won’t happen again. And to many, Gruntruck might’ve been the most natural and authentic band of the bunch.

Get off your cross and dance!

Gruntruck’s Push is finally being issued on vinyl for the first time domestically on Record Store Day (June 12, 2021). It’s a two-LP set with enhanced packaging. Two bonus tracks. Remastered by Jack Endino. Courtesy of Real Gone Records, in association with Rhino Records and Universal Music.

Matt Vaughan is the former manager for Gruntruck and the owner of Seattle's Easy Street Records. He lives in Seattle.

Previous Feature

How Push Came to Shove: the Little-Known Rise of Gruntruck, Part One