“Going Out of Business Since 1988!”

How Sub Pop – the label that brought you Nirvana and the Shins – survived constant money woes (rubber checks!), drunken rock stars (microbrews!) and grunge-era insanity (flannel!)

Originally published in the July 2008 issue of Blender. Republished with permission.

The birthplace of the record label that will forever be linked with the Seattle Sound—better known as “grunge”— isn’t in Seattle at all. It’s actually an hour to the southwest, in the liberal enclave of Olympia. It was there, in early 1980, that an impoverished Evergreen State junior named Bruce Pavitt, armed only with “an X-acto knife, a glue stick and a box of crayons,” put together a fanzine dedicated to the ultra-obscure regional punk scenes of the day: Subterranean Pop. With issue No. 5, Sub Pop (as the zine came to be called) morphed into a label of sorts, taking the form of a cassette compilation of underground bands from far-flung American cities.

Pavitt relocated to Seattle in 1983, in the pre-dot-com dark ages, when no one outside Washington had so much as heard of Starbucks. Four years later, he hooked up with an investor, local concert promoter and radio-show host Jonathan Poneman, to release Screaming Life, the debut EP from future alt-metal heroes Soundgarden, on Sub Pop Records. The two cemented their partnership in early 1988, when Poneman bought a 50 percent stake in the label from Pavitt with $19,000 he got from cashing in his savings bonds.

The ensuing years brought bankruptcy scares (too many to count), madcap schemes, the shocking death of a beloved rock icon, an uprising that tore the label founders apart—oh, and nearly 800 singles, EPs and full-lengths from Mudhoney, Nirvana, the Shins and the Postal Service, to name just a few.

In mid-July, Sub Pop will mark its 20th anniversary by throwing itself a two-day rock festival that spans its history and sound, from reunited grunge pioneers Green River to sensitive folkie Iron & Wine. And exactly why is a label that dates back to 1980 celebrating its 20th anniversary this summer? We’ll let them explain…

“SEATTLE’S GONNA TAKE OVER THE WORLD!”

Bruce Pavitt (cofounder) April 1, 1988, is when we quit our day jobs and moved into our tiny, original office, in the Terminal Sales Building downtown. It’s the first day of Sub Pop, with a big asterisk next to it: Except for the previous eight years.

Jonathan Poneman (cofounder) By May 1, 1988, we almost had to close down. We were building a company with practically no capital. One of our mottos was “Going Out of Business Since 1988.”

Charles Peterson (early office manager and unofficial house photographer)When we got paid, everyone would literally run down to the bank. If you were last in line, your check might bounce.

Mark Arm (founding Green River member; current Mudhoney frontman and Sub Pop warehouse manager) The elevator stopped at the 10th floor, and they were on the 11th, so you had to take an extra set of steps. It was a pauper’s penthouse.

Peterson The bathroom was the warehouse. You had to slide sideways through boxes of Green River’s record to take a leak.

Pavitt On our compilation Sub Pop 200, there was a picture of the building, and it said sub pop world headquarters. People were like, “Wow, they’ve got this 11-floor office building!” Part of our shtick was that we were this huge player on the West Coast. We came out with T-shirts that said world domination. We were ironically undermining corporate culture.

Chris Cornell (Soundgarden frontman) I remember running into Bruce around 1988, and I mentioned how there just suddenly seemed to be so much talent in Seattle. He put his arm around me and had this funny, confident look in his eyes. He said, “Seattle’s gonna take over the world!” He was being tongue-in-cheek, but not really—he seemed serious about it.

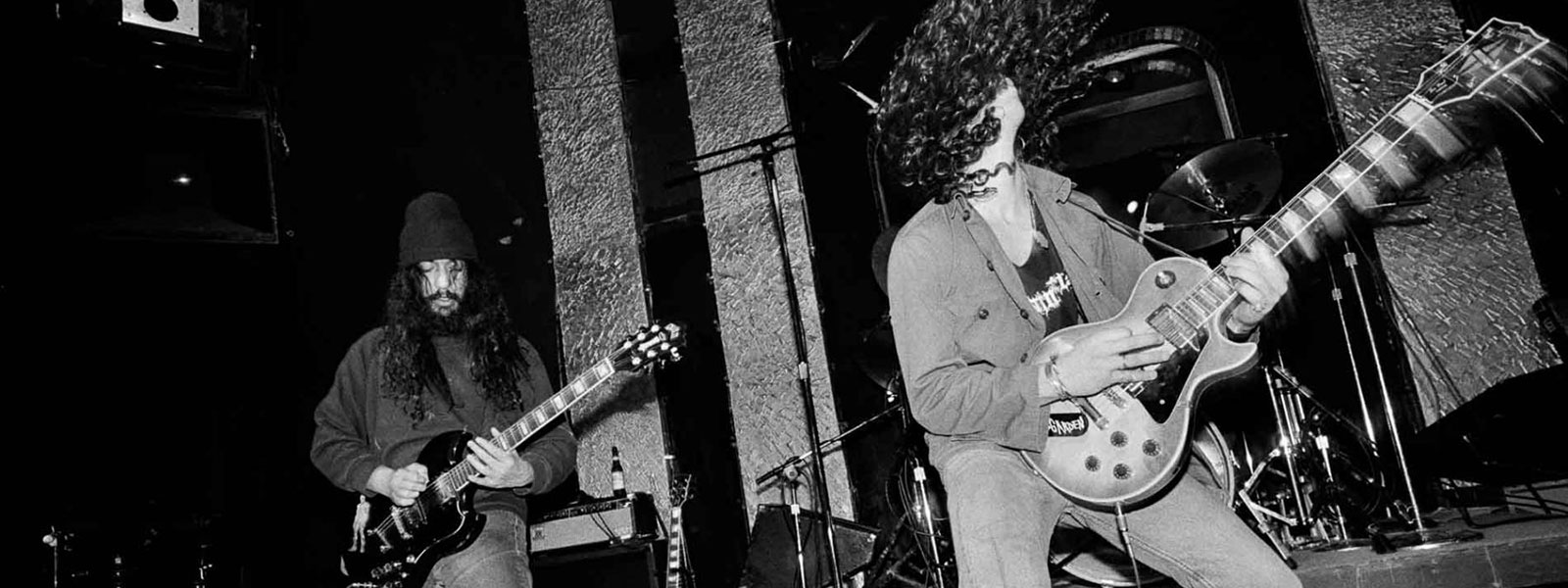

Sub Pop became known for its arch sense of humor (early T-shirts advertised the wearer as a loser) and its Barnumesque marketing savvy. Pavitt (the creative guy who favored edgier bands) and Poneman (the business guy with more commercial taste) modeled Sub Pop after iconic labels like Motown, whose product had a distinct look and feel. Charles Peterson took the dynamic live cover shots; Jack Endino produced the bands.

Jack Endino (early, unofficial house producer) Nobody was paying attention to Seattle—it was like a little, isolated germ culture. There were a bunch of punk fans who had gone back and discovered ’70s psych and ’60s garage and combined it with that punk energy and do-it-yourself spirit.

Arm A lot of touring bands would skip Seattle, so we had to entertain ourselves. No one was dreaming of the brass ring. I just wanted to keep our music loose and simple and fucked up and fun—that was helped along by beer and MDA [a variant of Ecstasy].

Megan Jasper (receptionist, 1989–1991; now vice president) Seattle was the exact opposite of where I came from, Boston, which was really uptight. The Mudhoney guys were a blast to be at shows with: They were fun, they were friendly, and they were drunk.

Poneman I knew if bands like Mudhoney and Nirvana could get heard, they’d be huge. They were just really good and charismatic.

Arm One of the label’s biggest tricks was selling itself so that people would want to get anything on Sub Pop, whether it was good or not, because of the packaging and the label identity. They came up with the Singles Club, getting people to pay [$35 a year] upfront without knowing what they were getting. That helped them stay afloat.

The first Sub Pop Singles Club release was “Love Buzz”/“Big Cheese,” by the then little-known Nirvana. In December 1988, Nirvana entered the studio to record their debut, Bleach, with Endino. But first, there were some legal matters to attend to …

Pavitt I was at a party next door to my house when I got this intuitive feeling, like, I really gotta go back home. Right as I did that, [Nirvana bassist] Krist Novoselic was walking up my stairway. He’s inebriated and he’s intimidating and he’s demanding a contract. It was very scary. I called up Poneman and said, “I know we don’t have contracts on any bands, but we need to get this guy one.”

Poneman Krist seemed like he could go off. He didn’t really know who we were, and stories about corrupt label people are legion. I sat up for a couple nights and composed a three-record contract largely taken from music-industry books.

Pavitt That contract ultimately allowed the label to survive. Krist coming over to kick my ass was the biggest blessing of my life. In March 1989, Sub Pop flew Everett True, a writer for the U.K. weekly Melody Maker, to Seattle to cover the burgeoning scene.

Poneman It’s a total misconception that we dreamed up flying Everett over here. It was an opportunity offered by a publicist for our distributor. We came up with the dollars, though—back then, scrawny indie labels weren’t doing things that were so calculated.

Pavitt I thought that people in Europe would get excited about American music if the bands actually looked or felt more authentically “American.” So we played up the “backwoods” vibe.

Everett True (former Melody Maker reporter) Everyone in Seattle was lying to me, but I didn’t care. If they wanted to portray [TAD’s] Tad Doyle as some kind of chainsaw-toting, dopesmoking, backwoods redneck, that was cool by me.

Tad Doyle (ex-TAD frontman) It was fun and effective, but hyping me as a 300-pound lumberjack painted my band into a corner.

Charles R. Cross (author of Kurt Cobain bio, Heavier Than Heaven) Kurt hated that he was presented as an inbred logger. Bozos like Everett True played into that.

Poneman Everett used the word grunge, which he got from the catalogue description of Green River’s Dry As a Bone that Bruce wrote: “ultra-loose GRUNGE that destroyed the morals of a generation.” None of us made up the word; it just became the tag that fit. Thanks in part to True’s articles, Sub Pop bands blew up in Britain, then Europe. Meanwhile—recurring theme alert!—there were money problems back at home. Frustrated, in 1991 the label’s two top bands, Nirvana and Mudhoney, defected to the majors.

Poneman The bands would see records being sold and they’d go, “Where are my royalties?” Never mind the fact that we had bought them a van, flown them to Europe, advanced them rent.

Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth guitarist) When I first saw Nirvana play, they had no money but destroyed all their equipment onstage. I was like, “How are you gonna finish your tour?” Bruce was figuring out how to get their shit fixed every night.

Arm Every once in a while, I’d go, “Bruce, I really need some money.” And he would cut me a check. Sometimes he’d go, “I really shouldn’t do this,” because by this point I was doing a lot of drugs.

Pavitt When Steve Turner of Mudhoney came in saying, “Jon said I could get my check for $5,000 today,” I started laughing, kind of a nervous laughter, because we had maybe $20 in the bank. Based on that conversation, Steve said, “Well, fuck you, we’re going to Warner.” I remember breaking down and crying in front of him.

Poneman We were lying to bands, but we were lying to ourselves as well—by being overly optimistic about when money would come in. We didn’t have even rudimentary bookkeeping knowledge.

Greg Dulli (Ex–Afghan Whigs frontman; now half of the Gutter Twins) The Whigs moved to L.A. to work on our second record. Then the label ran out of money. Around then, Sub Pop came out with T-shirts that said “What part of we have no money don’t you understand?”, which I’m sure was pretty funny, but I got stranded in L.A. and had to get a job.

“A TOTAL FEEDING FRENZY”

By summer 1991, Pavitt and Poneman had laid off nearly all their staff. Their fortunes changed dramatically after Nirvana released their blockbuster major-label debut, Nevermind, in September.

Poneman Without that contract with Nirvana, we wouldn’t have gotten the [buyout] deal from Geffen. Nevermind’s success did a lot for Bleach sales; plus we had a participation in the Nevermind sales and then eventually In Utero sales.

Pavitt By Christmas ’91, Nevermind had sold 2 million. We went from not being able to pay our phone bill to getting a check for half a million bucks.

Endino In the early ’80s, ambitious musicians would move to L.A. But 10 years later, people were moving to Seattle because they thought, Everyone and their mom is getting a major-label deal here.

Arm Cameron Crowe put Mudhoney on the Singles soundtrack, and in typical wiseass fashion, we wrote [the scene-eviscerating] “Overblown.” Were the lyrics [“And you’re up there, shirtless and flexin’/Display of a macho freak”] really inspired by a Soundgarden video? Well, Chris Cornell was taking his shirt off from day one. It just seemed kinda gross, like, I’m a good-looking model rock guy. But if I had it to show, I’d probably do it, too.

Cornell We toured together after Mudhoney wrote that song. It was nothing I paid much attention to.

Kim Thayil (ex-Soundgarden guitarist) The Vogue spreadabout grunge fashion was pretty damn crazy. There were models walking the runways in Milan wearing flannel.

Jasper A New York Times Styles reporter called up Jonathan about a “grunge lexicon” sidebar, and Jonathan redirected him to me. I was working for Caroline Records from home and was flying on three pots of coffee. I told the reporter, “Give me words, and I’ll give you the grunge translation.” I kept escalating the craziness, because anyone in their right mind would go, “This is bullshit,” but he never did, and it was printed. My favorite was “Swingin’ on the flippety-flop,” which meant hanging out. [Seattle’s] C/Z Records printed up a T-shirt with my word lamestain, which meant an uncool person. When the Times caught wind of the joke, the Styles editor called to yell at me. And then she asked me where she could buy the lamestain shirt.

Nils Bernstein (publicist, 1991–1997) Reporters would call us wanting an entertaining quote from Sub Pop about heroin use. A small number of very high-profile people, like Kurt Cobain, used it, but 99 percent didn’t.

Arm The “grunge era” got insanely absurd. The absurdist thing was that one of the main players decided to blow his head off.

Bernstein The day Kurt’s body was found [April 8, 1994] was horrible. It was total media insanity. There were news crews who somehow got up to the roof deck around the penthouse and then tried to get up to the next level—literally scaling the walls of this building—so they could film inside the office. The next day there was a TV reporter hiding in the bushes at my home.

Pavitt After the suicide, we sold half a million copies of Bleach. How do you comment on that? It’s like a trick question. It was a weird feeling that because of the suicide you’re able to pay your bills.

Buoyed by Nirvana cash, Sub Pop expanded quickly. But with alternative rock now a hot commodity, the label found itself competing with the majors. In January 1995, Sub Pop entered into a joint-venture agreement with one of those majors, Warner Bros. Under the terms of the deal, reportedly worth $20 million, Warner received a 49 percent stake in Sub Pop.

Pavitt There was a total feeding frenzy; major labels were approaching all of our bands. I remember our A&R head at the time said, “There’s this group the Grifters who have typically sold 5,000 records and would like a $5,000 advance,” and I’m thinking, That sounds about right. By the time we were done negotiating, we had given them a $150,000 advance. And they wound up selling 5,000 records.

Lou Barlow (Sebadoh frontman) With Sebadoh’s third Sub Pop record [1996’s Harmacy], things just went wrong. They’d hired people from big labels to do radio promotion and get placement for us on shows like Friends. They were trying to get our wannabe-hit single “Willing to Wait” to play when Ross and Rachel were splitting up or something. They lost a lot of money on us.

Pavitt I couldn’t relate to the corporate culture, so I officially resigned in April 1996. In December, some employees came to me and said, “Bruce we really miss you, and the company is becoming unbearable.” This was the beginning of [an attempted] mutiny, which is known as “the coup.”

Poneman Sub Pop was not a very nice place to work then. The company was exceedingly bloated.

Pavitt Jon had set up a meeting with Warner to get a bunch of money. My point was, before we borrow more, let’s think about restructuring and reconsidering how money is spent. I still owned 25 percent of the company and told him I was going to go to Warner and tell them to stop funding the label. Jon was extremely pissed off. He then fired the four people I wanted put in positions of more responsibility.

Bernstein I was one of the four fired [in early 1997]. Around that time, we had written, but not yet sent, a letter to Warner about changes we wanted. I understand why Jonathan did it—we were undermining him.

Poneman I may have overreacted, but these people were meddling in my affairs.

Pavitt After that, I didn’t really communicate with Jon, except through attorneys, for seven years.

“WE PULLED A RABBIT OUT OF A HAT”

When “the coup” went down, Sub Pop was in the midst of what are commonly referred to as the “dark years.”

Jasper People were afraid of getting fired. And, with Sub Pop trying to define itself post-grunge, the roster was all over the map— from Plexi, who were glam, to the Blue Rags, who were blues.

Poneman The coup was a wake-up call. It set us on a course of shrinking and becoming more efficient, which a lot of record companies are now doing. Jasper I came back to the label in 1998. The years 1999 to 2000 were all about Sub Pop finding stability. Bruce once said, “The amazing thing about Sub Pop is that this label has a knack for always pulling a rabbit out of a hat.” The big rabbit was the Shins.

Isaac Brock (Modest Mouse frontman; A&R, 2003–2005)I was an A&R person there before I actually had my job as an A&R person there, just from being around the office. I played the new Shins single for Jonathan. He said, “Get a hold of them. Sign them.”

Tony Kiewel (head of A&R) That’s not how I remember it. Zeke Howard, the drummer from Love as Laughter, had brought us the Shins demo after playing a show in Albuquerque.

Poneman Who cares? They both found them.

Jasper The Shins gave Sub Pop a record [Oh, Inverted World] that sold a ton and then gave us two more. But they did something greater than that. In 1998, I never saw anyone at work wear a Sub Pop T-shirt. Once we had Oh, Inverted World, a record everyone felt they could stand behind, people started wearing Sub Pop shirts again.

Even with most of the industry in free-fall, Sub Pop has managed to post profits every year since 2003. Electro-pop duo the Postal Service’s 2003 disc Give Up became Sub Pop’s second-best-selling album after the platinum Bleach, moving 920,000 units to date, and last year the Shins’ Wincing the Night Away entered the Billboard charts at No. 2, the highest-ever debut for a Sub Pop release.

James Mercer (shins frontman) Our debuting at No. 2 showed how utterly the industry had changed. Sub Pop was in a strong position because everyone else had their heels cut.

Jasper We’ve done well by responding to industry shifts—we’re not just a machine that just cranks out records and markets everything the same way—but we’ll continue to have big challenges surviving.

Poneman Sub Pop’s legacy? It’s one of the greatest indie labels out of the Pacific Northwest. World domination is an afterthought.

Pavitt My relationship with the label now is good; they’ve asked me to sit on a new board of advisors. Sub Pop has become huge—much larger than I could have ever imagined back when I was coloring in those fanzines with crayons.

Arm Mudhoney came back to the label in the late ’90s. It feels more professional now. Sub Pop was fuckin’ winging it 20 years ago. No one knew how royalties worked, no one had a contract—it was just, “You wanna put our record out? Sure, let’s do it.”

Thayil I’m looking forward to the 20th-anniversary show. I’ll be wearing flannel. Not really, but I imagine somebody will be.

Mark Yarm is a freelance writer for Wired, Rolling Stone, among others. Follow him on Twitter at @markyarm.