The Grunge Years: Sub Pop and the Quest toward World Domination

Even before Nirvana made them rich, Sub Pop founders Jonathan Poneman and Bruce Pavitt always had big goals for their label. This excerpt from Gillian Gaar's World Domination: The Sub Pop Records Story looks at the early days of the influential label

This is an excerpt from the Gillian Gaar book, World Domination: The Sub Pop Records Story. Republished with permission.

For Sub Pop, 1988 was a year of many firsts: our first office, our first employee, our first bounced check(s)—and that was just April! Jon Poneman, Sub Pop catalog description for Sub Pop 1000, 2013

When Bruce Pavitt sat down to write his first “Sub Pop U.S.A.” column of 1988, he was eager to promote the thriving creativity he saw around him. “1987: Hey, did it suck or what?” he observed, in a column entitled “27 Reasons Why Washington State Is a Cool Place to Live.” “Maybe for the rest of the country, but not around here. 1987 was easily the best year for local music since Bing Crosby rocked Tacoma. And that was back in ’38.”

“By ’87 and ’88, I was really convinced that the Seattle music scene was an incredibly happening music scene,” he says. “I was going to a lot of shows, I was seeing the stuff first hand, I was starting to release some of these records. And when you go through that list [in the column], it doesn’t even have Nirvana on it, you know? No Nirvana, but Screaming Trees, Soundgarden, TAD, the Fastbacks, Girl Trouble, the U-Men, Young Fresh Fellows, the Melvins—this is amazing stuff . So many of these bands went on to have cult followings or really helped to influence culture. And again, this is before Mudhoney or Nirvana, the two bands that really helped blow up the scene.”

World Domination: The Sub Pop Records Story will be in stores on November 20.

Despite Bruce’s optimistic boosterism, Sub Pop was actually on shaky ground as 1988 dawned. Soundgarden would release one more record on Sub Pop, but they had already signed a one-album deal with Los Angeles–based SST Records. “It was disappointing but understandable,” says Bruce. “SST was very influential at the time.”

And, to Bruce and Jon [Poneman]’s further dismay, they’d lost another valuable asset when Green River broke up in late 1987. After Steve Turner’s departure from the group, a schism in the remaining members’ musical interests had developed; Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard wanted to pursue a more commercial direction, while Mark Arm favored a raw, indie-rock style. The band had nonetheless continued working on Rehab Doll, but the final night of their 1987 West Coast tour brought Green River to a sudden end.

On October 24, the group had opened for Jane’s Addiction at a Los Angeles club called the Scream. Jeff had put several A&R reps on the band’s guest list, to Mark’s dismay; he’d wanted to invite more friends. Only one rep showed up, too late to catch the band’s set, which was perhaps just as well, as Mark had blown out his voice at the previous night’s show in San Francisco. And while Jeff and Stone were excited by Jane’s Addiction, who’d drawn a crowd of two thousand without even having a record deal, Mark was unimpressed; it was obvious the musicians were no longer compatible. Back in Seattle, when Mark and Alex Vincent arrived for a practice session on Halloween, Jeff, Stone, and Bruce told them they were out of the band.

Mark quickly rebounded. That same evening, he ran into Dan Peters, the drummer in Seattle band Bundle of Hiss, at the OK Hotel, and told him the news. In short order, Mark, Dan, and Steve Turner were soon jamming together; they then found a bassist in Matt Lukin, who’d been kicked out of the Melvins (Buzz Osborne and Dale Crover had told Matt they were breaking up the band, then moved to San Francisco and started it up again without him). The new band took their name from a Russ Meyer film that had recently played on a Meyer triple bill at Seattle’s Neptune Theatre: Mudhoney.

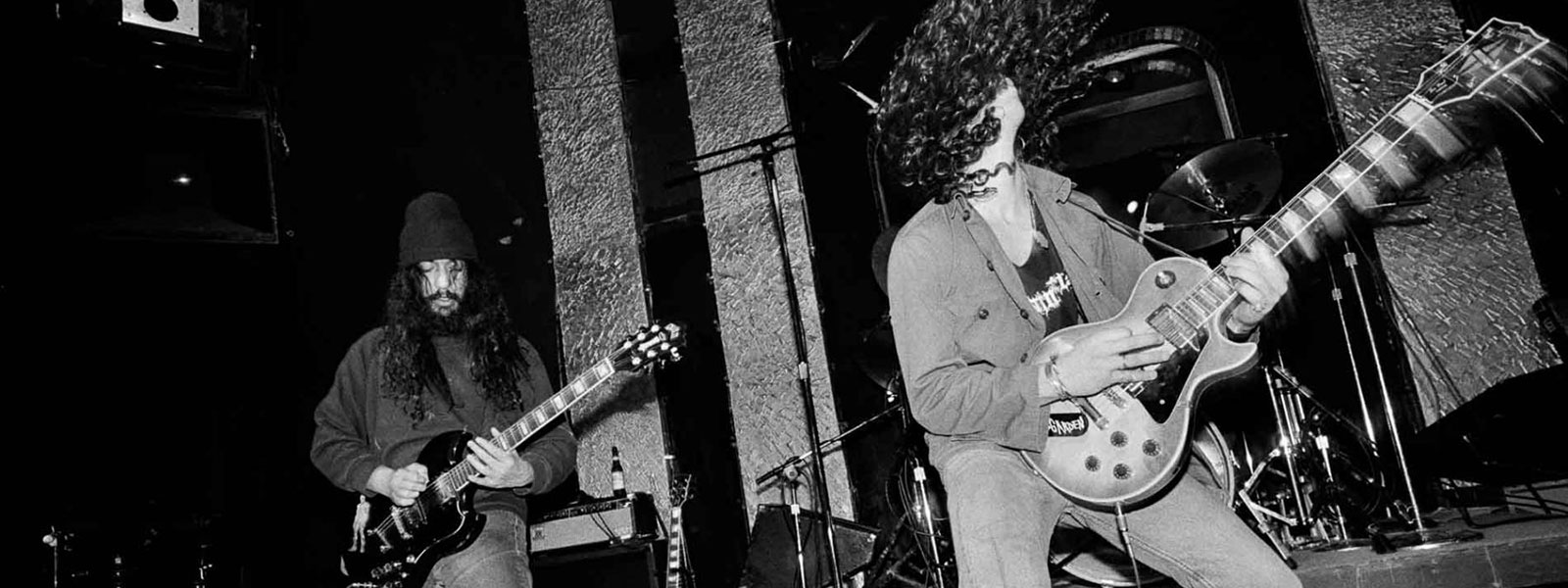

Sub Pop would not exist without Mudhoney. Bruce Pavitt

Mark brought in the band’s demos to play to his co-workers at Muzak. Bruce quickly recognized the band’s potential and sent them into the studio. “Mudhoney is the band that really launched Sub Pop,” he later said. “Sub Pop would not exist without Mudhoney, would not have happened without Mudhoney … they were absolutely brilliant immediately, so it was our good fortune, our good grace to have this amazing band come together right as we were trying to launch the label.” That view was confirmed when the band played their first show on April 19 at a Seattle club called the Vogue. “It was just astounding,” Bruce recalled. “They were brilliant … and their live shows were very spontaneous, very physical, very funny. They really epitomized the spirit of Sub Pop, which really had a lot to do with humor—humor in rock ’n’ roll. They were definitely the flagship band there for quite a while.”

By then, Bruce and Jon had seen another band they’d soon add to Sub Pop’s roster: the band whose demo Jack Endino had recorded in January ’88, who were now calling themselves Nirvana. Jack had made copies of the band’s demo and passed one to Jon, who immediately fell in love with the first song, “If You Must.” (Ironically, Kurt Cobain disliked the song, and the band soon dropped it from their set list.) Bruce felt otherwise, having played the tape at Muzak, where it received a less-than-enthusiastic response: “The general consensus was that Kurt was a good singer, but the material really wasn’t very good.” He was no more convinced when he and Jon caught a sparsely attended show at Seattle’s Central Tavern, feeling the group had no stage presence. He agreed to release a single, but insisted it had to be the band’s cover of “Love Buzz,” originally recorded by Dutch act Shocking Blue (best known for their 1969 hit “Venus”), as he didn’t think Nirvana’s original material was strong enough.

In March, Bruce and Jon took a big step and quit their day jobs. Sub Pop had acquired its first office, in the penthouse of the Terminal Sales Building, at 1932 First Avenue in downtown Seattle, for a rental fee of $200 a month. “It was a bold move,” says Bruce. “It’s when we really started to go into it professionally. Even though we weren’t necessarily that professional in our execution, it was a pretty big leap for us. It sure felt good to quit my job at Muzak. It was a blessing that we both had really crappy jobs!” They formally took over the lease on April 1, 1988; henceforth, April Fools’ Day would be designated as Sub Pop’s official anniversary date.

The Terminal Sales Building, aka Sub Pop World Headquarters

Though being in the “penthouse” sounded glamorous, the reality was more mundane. The elevator stopped at the tenth floor, meaning you had to walk up a flight of stairs to actually reach the office. And the space was hardly palatial; in lieu of storage rooms, record stock had to be stashed in the bathroom.

Being in business full time was more challenging than Bruce and Jon realized. By the beginning of May, they’d gone through most of their money, leaving them unable to pay the printing bill for the Rehab Doll sleeve. Bruce persuaded the printer to give them the sleeves on credit: “If he didn’t advance us the sleeves, the printer would be stuck with them, as we wouldn’t be able to pay until we actually sold some of the records.”

The company’s motto, “Going out of business since 1988,” was meant as a joke, but it was rooted in truth. “In the early days, it was barely managed chaos,” remembers Daniel House. Skin Yard’s bassist had just quit his day job at a printing shop, and, on the way home, had ended up giving a lift to Jon, whom he’d seen waiting at a bus stop. On learning that Sub Pop was looking for someone to handle sales, he quickly offered his services.

“Things were growing at a rate that Bruce and Jon themselves could barely keep up with it,” he continues. “They were really bad with money and they were pretty fucking disorganized. They were always kind of scattered between too many things, and weren’t particularly good at time management. But they were also the cat with nineteen lives. It amazed me how they could make some of the biggest blunders and it would just turn around and somehow benefit them.” Sub Pop’s ability to weather innumerable storms yet somehow land upright would serve them in good stead in years to come.

Charles Peterson, who’d been hired as Sub Pop’s receptionist, among other duties, also found the first months to be “pretty tenuous. Especially when payday came around, and whoever was first in line at the bank could maybe cash their checks. I remember I handed out the envelopes with the checks, and would be like, ‘See you guys!’ and run down to the bank and get first in line.”

“I think there was a long period when they were just trying to figure out what this was going to be,” says Nils Bernstein, the music fan who had picked up the Sub Pop cassettes and was now running his own record shop in Seattle, Rebellious Jukebox. “It was this kind of incremental thing. They’d put out one record, you didn’t know if there would be another record. And it was singles without picture sleeves; it was as bare bones as it could be—they were given away at shows! The early mythology around Sub Pop was that from the very beginning, they said, ‘These are amazing bands, and you’re missing out if you’re not on board!’ and made it out to be this massive scene. But then, like positive new age affirmations, it turned out to be true.”

For his part, Bruce hoped an esprit de corps would develop at the burgeoning company, despite the business difficulties. “When you’re working together, when you’re running a mom-and-pop business, which is what Sub Pop was, it’s essentially an extended family,” he says. “Half the time you can pay your bills, half the time you can’t, and the only thing that’s going to keep you together is just a sense of trust and camaraderie, and an underlying understanding that we value this culture and we’re all just going to do whatever it takes to make it happen.”

“As cliché as it is, there was that kind of Mickey Rooney, ‘Hey, let’s put on a show!’ kind of thing,” says Charles. “We all just wanted to do it, just to do it. It wasn’t this moneymaking operation at all.”

If Sub Pop didn’t have much capital, the company did have something else: an established brand. And Bruce realized you didn’t need to have a lot of money to enhance that. He’d noted that labels like UK-based Factory and 4AD had cultivated a specific look and sound, which he didn’t see happening among stateside indie labels. While working at Bombshelter and Fallout, he’d seen customers buying records simply because they were on a particular label. He wanted to generate the same kind of excitement about Sub Pop’s releases. “There was a real emphasis on giving focus to the graphics, and maintaining a certain uniformity with the sound through the production of Jack Endino,” he says. “I thought that was key as far as establishing a label identity.”

One of Sub Pop's first vinyl releases, Soundgarden's Screaming Life EP

Appealing to collectors was another strategy, with limited-edition runs of releases on colored vinyl. The first six hundred copies of Soundgarden’s Screaming Life EP were on orange vinyl; the first eight hundred copies of Blood Circus’s first single came on red vinyl; the first six hundred copies of Swallow’s first single came on yellow vinyl. A determined collector would have to acquire all of them.

Bruce and Jon were also keen to get Sub Pop’s name out there in any way possible. “There were a lot of labels or artists who wouldn’t think of doing an interview for the Costco newsletter, but we would do that,” said Bruce. “We had this philosophy that we would never turn down an interview for any reason or anybody. We wanted the name Sub Pop to just permeate the culture.”

Humor was also a key factor. Sub Pop’s promotional efforts were decidedly tongue-in-cheek, parodying the corporate culture the label’s co-founders had just escaped from at Muzak. In their imaginations, Sub Pop wasn’t a business struggling to keep its doors open, but a multinational corporation on its way to what Bruce and Jon were sure would be “World Domination.”

“I was writing the ad copy for Sub Pop, with a hype style that was coming into practice towards the end of my ‘Sub Pop’ column,” Bruce explains. “Jon and I both shared a self-deprecating sense of humor, as did Mark Arm. I think we all felt that the punk scene was taking itself too seriously at the time, so we approached the label with a sense of the ridiculous.” Bruce’s business card gave him the title of “Corporate Magnate.” Jon’s read “Corporate Lackey.”

The iconic “LOSER” T-shirt allowed the label’s fans to join in on the fun. “I remember saying we needed to have a Sub Pop shirt with ‘LOSER’ emblazoned on the front and the Sub Pop logo in back,” says Bruce. “It was brought to my attention recently that Mudhoney manager Bob Whittaker used to wear a T-shirt with ‘Loser’ on it, so give credit to Bob. As with any culture, ideas are traded back and forth. The bold black lettering of ‘LOSER’ complemented the logo, and was part of the vibe.”

Bruce and Jon were also pleased at the message the shirt sent during a decade so devoted to conspicuous consumption. “It was a real anti-yuppie statement,” Jon proudly told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

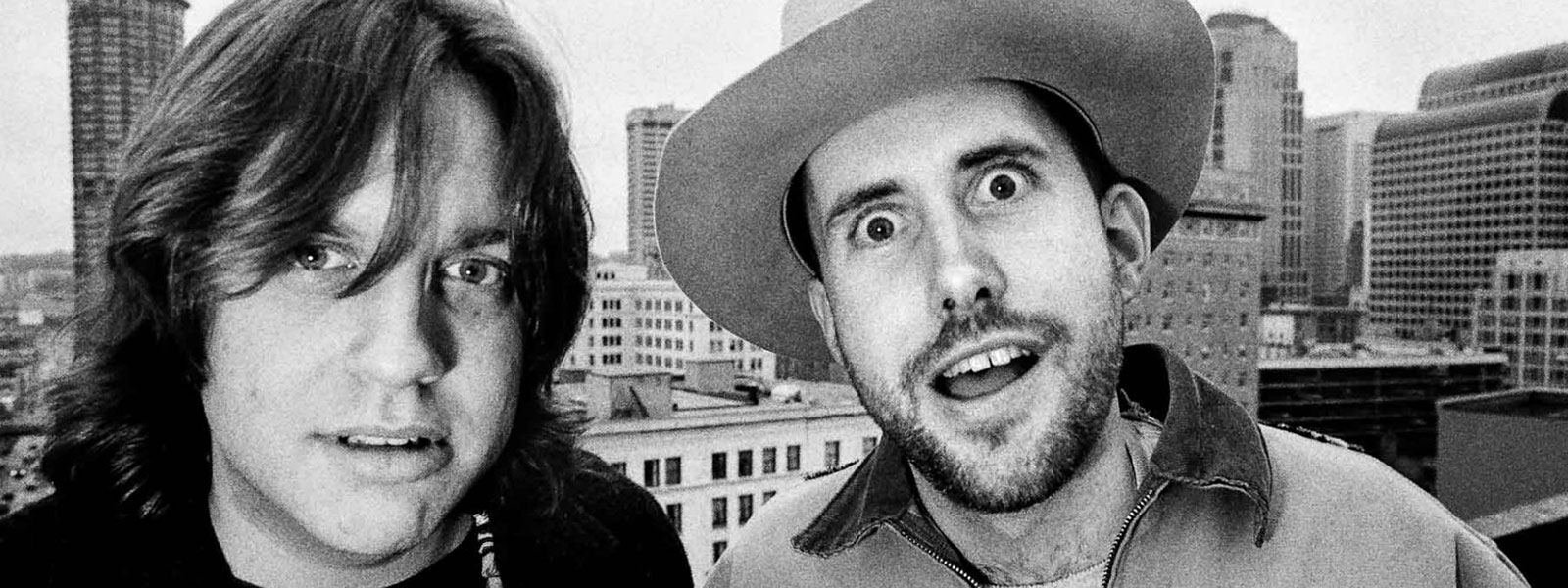

Poneman and Pavitt in the office

This freewheeling spirit was evident in the company’s other business dealings as well. Like many small labels, Sub Pop often had difficulties being paid promptly by the companies that distributed its records. In July 1988, while attending the New Music Seminar, a music industry event in New York City, Bruce and Jon dropped in at the offices of one of their distributors, Caroline Records, wearing T-shirts bearing the inscription “YOU OWE ME MONEY.” “We never brought up the bill once the entire time,” Bruce recalled. “And by the time we left, they handed us a big fat check.”

Beneath the humor was an unwavering faith in their product. “I did sincerely feel the Seattle scene was going to blow up—but not to the degree it did,” says Bruce. “I was thinking about the impact that Detroit had in the late ’60s, early ’70s, with the Stooges and MC5. I felt we were on a similar trajectory.”

Just three months after Sub Pop officially opened its doors, Bruce received confirmation that they really were on to something. A music fan from Brooklyn, Ed McGinley, called Sub Pop’s offices and ended up talking to Jon about records. Jon happened to mention that there was a great show coming up: Soundgarden, Mudhoney, and the Fluid were playing the Central Tavern on July 2. “And this guy got on a Greyhound bus and traveled three thousand miles for this show!” Bruce marvels. “I tell people that that was the moment where I realized—this scene is about to blow up. If people are willing to get on a bus and travel three thousand miles for a show, they’re getting it.’

“They’re realizing that there is something happening here that isn’t happening in other parts of the country.”

Read the whole story in Gillian Gaar's book, World Domination: The Sub Pop Story. Available in bookstores and online on November 20.

Gillian Gaar, a longtime Seattle-based writer, draws on firsthand interviews, deep research, and her years of covering that city’s scene as a music journalist to bring together the first in-depth historical narrative of one of America’s most influential independent record labels. Gaar is the author of more than 15 books, including She’s a Rebel: The History of Women in Rock & Roll, Return of the King: Elvis Presley’s Great Comeback, and Entertain Us: The Rise of Nirvana. She was a senior editor at the Seattle music paper The Rocket and has also written for Mojo, Rolling Stone, Goldmine, and Seattle’s Museum of Popular Culture, among many other publications and organizations. Gaar served as a project consultant on Nirvana’s With the Lights Out box set.